Dimitris Troaditis. “Anarchist Dimitris Karampilias (1872-1954)”

Dimitris Troaditis. “Anarchist Dimitris Karampilias (1872-1954)”

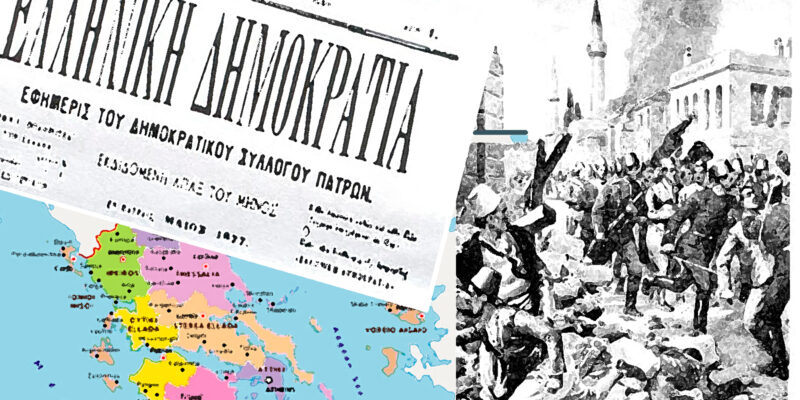

Dimitris Karampilias was born in the village of Mintilogli Achaia, outside Patras, in 1872. During the 1890s he was one of the most active anarchists in the “Epi Ta Proso” newspaper and collective and in the anarchist movement of Patras. After the dissolution of the anarchist movement of Patras, he moved to Athens with Giannis Magkanaras where they both participated in anarchist groups and activities.

In 1901, Karampilias settled in Alexandria, Egypt, where he worked as a cigarette maker and participated in the labor and anarchist movement. He collaborated with Greek and Italian anarchists who had settled there before him.

We do not know the exact time of Karampilias’ departure from Egypt or whether he returned to Greece. He went to France and worked as a tailor, becoming involved in the anarchosyndicalist movement there. Some sources suggest he associated with other Greek anarchists who lived and were active in France, although we do not know names or how many there were, and some sources have him participating in the printing of the anarchist magazine «Les Temps Nouveaux», edited by Jean Grave. He certainly became a member of the General Confederation of Labour (CGT) founded in 1906 in Amiens. At that time the Confederation was relatively more syndicalist and had not submitted to Marxist control. Shortly before the outbreak of World War I internal conflict broke out in the organisation after the adoption by the leadership of patriotic rather than internationalist positions. The anarchists and anarchosyndicalists members gradually began to withdraw, and it appears that Dimitris Karampilias regretfully left the CGT with his French companion Louise-Melanie Pierette. The couple returned to Greece in 1913 or 1914 and settled in Karampilias’ homeland Patras, where he continued to work as a tailor, and she taught French language.

According to one source, during the period of the Greek military campaign in Asia Minor Karampilias was actively involved in producing anti-war propaganda. The same source says that in the elections of 1920, which became a referendum against the war, he was urging people to vote for the Sosialistiko Ergatiko Komma Elladas (SEKE – Socialist Workers’ Party of Greece, predecessor of the Greek Communist Party) which during this time had adopted a clear anti-war program. Considering that during those years many anarchists were founders of communist and socialist parties in the belief that they may have a revolutionary potential, and considering also that one of the foremost organizers of SEKE in Patras was Stelios Arvanitakis, who shortly after became an anarchist communist, maybe it is credible that Karampilias supported voting for SEKE. However, from what we know, Karampilias was unlikely to have been a member of SEKE or involved in any organized socialist or similar movement in Patras before 1945. The well-known local left trade unionist Haralampos Ploskas said in early 1980 that during the 1930s Karampilias was the only anarchist in Patras.

In 1928 a publisher named Leon Panayotou published a book in Patras by a certain B. Konstand (?) under the title “Christianity”. It was translated from French by D. Karampilias, but we do not know the precise content of this book.

During the dictatorship of 4th August (1936), Karampilias was not bothered by the regime although he was well known to the authorities. He withdrew to his village home in Mintilogli and lived there until shortly after the war. He worked as a tailor, while his companion Louise taught French privately. There is some evidence that he was not involved in any activism at Mintilogli, but apparently he formed a circle of friends who gathered at his home to discuss general theoretical issues. Although Karampilias often introduced communist ideas, available evidence suggests that he did not talk about political parties, but rather about the lives of workers and peasants.

It appears that Karampilias was careful in his political dealings, and took strict precautions in that very difficult time when the free circulation of dissident ideas was illegal. A few selected participants met for discussions at his home in Mintilogli. Topics were not confined to Greek political affairs, but extended to international issues. Around fifteen people were included, mostly supporters of reformist socialism. It is significant that within this small political circle there were no young people. At the same time, however, Karampilias was in contact with at least ten young radicals. He discussed many issues with them, and although they sometimes disagreed with him, they saw him as modest and they respected him because he was “the first communist in the village”.

The extremism associated with the general secretary of the Stalinist KKE at the time, Nikos Zachariades, influenced many dissident young people. Almost all the youth who knew Karampilias politically became key figures in the Communist Party at the local level, but few occupied high ranking positions in the party, and many died in exile.

In 1945, after the riots of December 1944, a conference of socialists of all tendencies (except the Stalinists), was held in Athens. They decided to form the Sosialistiko Komma-Enosi Laikis Dimokratias (SK-ELD: Socialist Party – Union of Peoples’ Democracy), a mostly social-democrat body. University professor Alexandros Svolos was made president and Elias Tsirimokos general secretary. SK-ELD was joined by, among other groups, Epanastatiko Sosialistiko (Kommounistiko) Komma Elladas (ESKE: Revolutionary Socialist (Communist) Party of Greece), which became a separate councilist tendency. ESKE was founded in 1943 as a revolutionary socialist party which followed the views of Rosa Luxemburg. From the start they were in vicious conflict with KKE. Initially, ESKE was known by the name of their magazine “Nea Epochi” (“New Age”) which was circulated illegally with a similar magazine called “Sosialistiki Idea” (“Socialist Idea”). In autumn 1943, during confrontation with the Communist Party, ESKE changed their name to the Revolutionary Socialist (Communist) Party of Greece and began publishing “Kokkini Simaia” (“Red Flag”). In 1945, as described above, they joined SK-ELD.

After a speech by A. Svolos in Patras, a local Committee of SK-ELD formed in the city, and D. Karampilias became a member. In 1950, when the party restructured, D. Karampilias continued to be a member of this local Committee. Karampilia’s participation in the Prefectural Committee of SK-ELD in Patras is confirmed by Haralampos Ploskas in his book “Mia zoo agones” (“A life of struggles”), where he writes that Karampilias was “an old anarchist who in his old age became a socialist”. From our research we have come to the conclusion that the reason Karampilias participated in SK-ELD may have been that this party was clearly opposed to the civil war of 1946-1949, which Karampilias considered disastrous for any libertarian political developments in Greece.

One of Karampilias’ main pre-occupations during the late 1940s was reading the daily and various other newspapers coming from Athens into the offices of the Patras daily newspaper, “Imera” (“Day”). “Imera” began publication around 1952 and was a continuation of the newspaper “Simerini” (“Today”). In turn, “Simerini” had been launched shortly after the end of German Occupation as a “revolutionary” act after some journalists of the newspapers “Neologos” and “Peloponnese” went on strike. The journalists decided to launch their own newspaper.

Dimitris Karampilias developed a special friendship with the director and editor of “Imera”, Christos Rizopoulos, despite their age difference (the latter by then was around 40). Christos Rizopoulos was born in 1908 in Patras, and Karampilias knew him before the war. He was a member of the Communist Party and a journalist of its mouthpiece “Rizospastis” (“Radical’). He was author of the book “Memories of Kalpaki”, which in 1933 caused a stir among the Greek political establishment of the time. Rizopoulos did his military service in the late 1920s as an ordinary soldier in the Border Division VIII of Kalpaki, which was a special military centre and a kind of exile camp where communist soldiers were sent. His catalytic revelations through the pages of “Rizospastis” and in his book on Kalpaki camp resulted in the closure of this disciplinary camp in 1934. Christos Rizopoulos avoided involvement in the vicious conflict between Stalinists and Trotskyites that began in the early 1930s and left the Communist Party to find himself a broader liberal democratic space.

Old colleagues and acquaintances said of Karampilias that although he had not finished even elementary school, through self-education he came to understand various social, political, and historical issues. Those who remember him say that he read a lot, and always had a book in his hand.

After the end of German Occupation and the war D. Karampilias entrusted an important part of his manuscripts and materials to Marxist historian Gianis Kordatos. He also sent some letters to him. Why Karampilias should trust G. Kordatos is explained by the fact that Kordatos had been expelled by the Communist Party (KKE). Karampilias believed he was probably the only one who could preserve the historical memory of the old anarchist and working class movement in Greece. Dimitris Karampilias was not at all satisfied with contemporary written history nor with the available literature about the working class and socialist movement in Greece. He considered that most historical evidence had either been falsified or omitted. For this reason he began to write his memoirs. In 1954 he had almost finished and would soon begin publishing them as a series in “Imera” (“Day”). He was also ready to publish an article in that newspaper about the facts and realities of the attack by anarchist Dimitris Matsalis on businessmen Frangopoulos and Kollas in 1896 in Patras.

In addition to his memoirs and articles on the history of the labor movement, Karampilias translated theoretical articles by prominent anarchists. His translation of an article by Piotr Kropotkin titled “All socialists” was published in Patras’ daily newspaper “Simerini”. (Thursday, 14 March 1946). The dates of the translation and publication of this article are important because they coincide with preparations for civil war by N. Zachariades and the Communist Party. Karampilias opposed such preparations because although he had supported popular resistance against the occupying German army, he disagreed profoundly with a coup by the Communist Party which could result in a Stalinist-type dictatorship in Greece. He also translated an article by Victor Hugo under the title “United States of Europe – With Democracy and Socialism” which was also published in “Simerini” (Sunday, 25 November 1945).

D. Karampilias also engaged with literary and artistic subjects. Amongst the many articles he published was an article on Schiller and Beethoven in the Journal of Patras “Astir Tis Ellladas” (“Star of Greece”), on 6 February 1927. In addition, the editor Christos Rizopoulos used Karampilias’ personal historical archive to write two articles about the Chicago Martyrs of 1886. They were published in “Simerini” (Tuesday, 30 April 1946) and “Imera” (Sunday, 29 April 1979).

Dimitris Karampilias never published his work on Dimitris Matsalis. He died on 15 September 1954. He was 82. Christos Rizopoulos published an outstanding obituary on Sunday, 19 September 1954 in “Imera”.